“I have the impression that it was not FIFA that really organised the World Cup, but Mussolini.”

Jules Rimet

It is a well-established fact that Benito Mussolini expertly instrumentalised the second edition of the FIFA World Cup – the first on European soil – to legitimise his fascist regime. Less well-known, however, is that merely a few weeks later another World Cup was staged, a tournament organised as an anti-fascist counterweight to FIFA’s collusion with Mussolini: the 1934 Workers’ World Cup, hosted in FIFA’s birthplace of Paris.

The coupe du monde de football ouvrier was neither a novel idea nor was it the first proletarian international tournament. Encounters between working-class teams and associations from different countries were quite common in the early 20th century because they were seen as proletarian internationalism in practice, with the express aim of cultivating understanding and friendship between peoples; in the words of Nicolas Kssis, they “made the greatest impression and embodied the ideal type of politico-sporting propaganda.”

In Le Mondial ouvrier des années 1930, one of the most eye-catching examples of this is outlined: “Just after the Great War, the young [French] sports federation ‘Rouge’…thus made it a point of honor to meet teams from its German counterpart to display its refusal of the Treaty of Versailles, its desire to overcome the nationalist antagonisms ‘maintained by the bourgeoisie.'”

Kssis argues similarly and familiarises us with this topic further in Le mouvement ouvrier balle au pied: “Meetings between German and Alsatian working-class sportsmen were…one of the great classics of the interwar period. They allowed [Rouge] to maintain ongoing rapport with two very powerful workers’ sports federations, but above all to mark both its refusal of the Treaty of Versailles (in the Alsatian case) and the continuation of its pacifist image in the German case.”

Politics, understandably, sometimes got in the way: “The match which was held on November 11, 1923 at the Vincennes track, between a Parisian selection and an Alsatian team, entered into this tradition. Originally it was a question of organising a match “bringing German and French workers into fraternal confrontation.” But the political situation in Germany (the coup d’etat of Hitler and Luddendorf) prevented “eleven communist militants” from leaving Germany. It was, therefore, necessary to improvise [and organise] a substitution match with a team from Alsace.”

A year later, however, Germans finally managed to step foot on French soil for a game that nicely illustrated the virtues of workers’ football. In late 1924 – merely a year after the French occupation of the Ruhr – the erstwhile arch-rivals came together as a show of friendship in what was the first post-WWI encounter between German and French footballers – a prospect at the time vehemently opposed by the nationalist, bourgeois DFB, which was still flying the German Empire’s black, white and red at international games. After the match, the German worker-athletes from Dresden were lauded by the French press for their “honourable conduct,” having deliberately missed four unwarranted penalties.

Generally speaking, workers’ football set itself apart from its bourgeois counterpart by its more pronounced focus on fairness and camaraderie, instead of competitiveness, as illustrated by the above-mentioned application of the gentlemen’s rule of missing penalties on purpose if they had come about via questionable refereeing decisions or if the scoreline was already lopsided. Football, like workers’ sport in general, was supposed to strengthen the bonds of the working class and foster its health; players were not opponents but class comrades and, in many cases, colleagues.

While utopian to an extent, since neither competitiveness nor unruliness could ever be fully extirpated, this attitude nevertheless often manifested itself in the enactment of groundbreaking new rules. Goalkeepers, for example, were held in high esteem and enjoyed special protection. Thus, already in the 1920s and 30s, they were in some circumstances allowed to be substituted if they had sustained an injury – substitutions weren’t officially added to the Laws of the Game until 1958.

Elsewhere, too, new ideas were being implemented: high-stakes games or other big occasions in Germany of the 1920s saw the utilisation of goalline referees, better known these days as Additional Assistant Referees, to aid the main official. Writing for taz, René Martens once described the time the ATSB selection, the German workers’ national team, hosted the USSR in Hamburg in 1927 – a game that was even broadcast live over the radio – in which the Belgian centre referee was supported by a grand total of eight assistants.

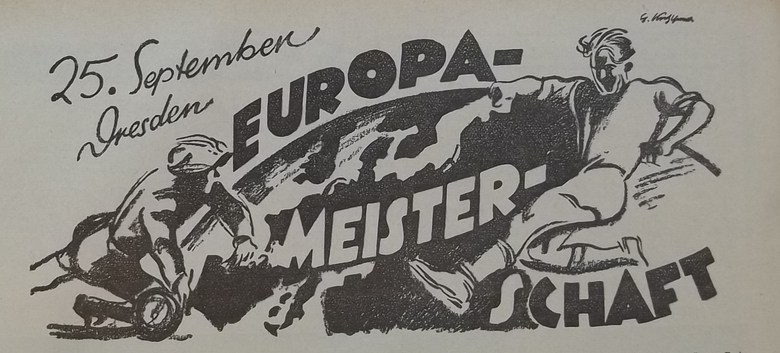

Over time, single transnational fixtures evolved into bigger events, and by 1934, there had already been several international competitions: the Olympiads, organised by the social-democratic Lucerne Sports International (LSI/SASI), as well as the 1928 All-Union Spartakiad in the USSR, hosted by the communist Red Sport International (RSI). While football was an integral part of these occasions, another workers’ tournament is more relevant to our discussion here: the 1932-34 European Championship.

Held by the LSI (in contrast to the World Cup, co-organised by the RSI), it was the first truly pan-European football contest. The idea for a competition on a continental scale had already been floated much earlier and it had found partial realisation in the UIAFA’s Grand European Football Tournament of 1911 and in the Central European International Cup, staged for the first time in 1927 by bourgeois football associations within FIFA, but these could not match the magnitude and diversity of the LSI’s Workers’ Euros. 15 countries, split into three groups, participated:

| Northern Europe | Central Europe | Western Europe |

| Denmark | Austria | Belgium |

| Estonia | Czechoslovakia (Sudeten Germans) | France |

| Finland | Germany | Netherlands |

| Latvia | Hungary | Switzerland |

| Norway | Poland | |

| Sweden |

The aforementioned rule of being able to substitute injured keepers was in force at this tournament, but this wasn’t the only innovation: unique, too, was also the timeframe during which the Euros were staged. Instead of the one-month tournaments of today, there was no fixed schedule other than that all group games should be finished by June 1, 1934, with kick-off times and localities chosen by the teams themselves. The final round, played out between the three group winners via two-legged ties, was then supposed to determine the European champions by the end of the year.

This, however, never materialised. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, German workers’ sport was brutally crushed, and the same occurred in Austria in early 1934. With the two sides who had opened this decentralised tournament in front of 28,000 in Dresden in September of 1932 eliminated, the European Championship was aborted without a winner ever being crowned.

In light of the rapid diffusion of fascism and the threat of war that followed in its step, and witnessing what was happening in Germany, Austria, the Baltics and elsewhere, the communist RSI, together with its French sister association, the Fédération sportive du travail (FST), organised the International Rally of Athletes Against War, also called the International Anti-Fascist Sports Rally, two months after the conclusion of the World Cup in Mussolini’s Italy. Staged in the traditionally proletarian neighbourhoods, the “red bastions,” of Paris’ 12th arrondissement, the Rally hosted some 50 teams from all over the globe, although the main event, the World Cup, was almost exclusively a European affair, the United States being the sole exception.

20,000 spectators witnessed the Rally’s impressive opening ceremony during which 3000 proletarian athletes from 18 different countries marched through the Stade Pershing in Bois de Vincennes. “The masses of these great days,” announced the communist daily L’Humanité buoyantly, “…testify to the appetite for workers’ sport – for true sport freed from all venality…from all bourgeois spirit, from all chauvinism – as well as ardent internationalism, which pits them against war and fascism.”

This wasn’t just a momentous occasion due to its pronounced transnational character but also because it signified a major rapprochement between communists and social democrats, at least in France. I already elaborated on the differences between RSI and LSI in my piece on workers’ club Dresdner SV last year, but for our purpose here, it needs to be recalled and borne in mind that these two were not in any way affiliated, and in fact, were gripped by a deep-seated hostility towards each other.

While there is no shared genealogy between the LSI’s Euros and the RSI’s World Cup, the fact that athletes from the former were invited to the latter proved conducive to the efforts of forming a Popular Front in France, though its overall international importance shouldn’t be overstated considering that LSI members had also been invited to the Moscow Spartakiad and this, at the time, had the complete opposite effect as many of those who participated were consequently expelled from the LSI. But of course, the political climate of 1928 vastly differed from that of 1934. Indeed, the altered global situation meant that the Comintern (and, by extension, the RSI) now officially sought reconcilliation with the reformist “social-fascists.”

As André Gounot explains in Les Spartakiades internationales, “the primary function of the Antifascist Sports Rally of Paris then became bringing together worker athletes from all organisations to take a step towards the total unity of the international workers’ sports movement, considered an important element of workers’ mobilisation against fascism. The LSI first gave an unfavorable opinion to the invitation made by the RSI, but softened its attitude a few days before the gathering: in a letter addressed to the Organising Committee…it points to the possibility of cooperation with the RSI, and lets it be understood that it no longer opposes the official participation of its sections in the Rassemblement de Paris.”

L’Humanité also noticed that this tournament would aid in bridging the gap between the two proletarian creeds: “At a time when the bourgeoisie is carrying out its hateful and demagogic campaign against foreigners…the young sportsmen will affirm by their united front that, whatever tendency they are attached to, the fraternity of the working class knows for them neither difference of race nor difference of language.” At the opening ceremony, communist athletes and their socialist counterparts, organised in the Union of Sports and Gymnastics Societies of Labor (USSGT), marched in unison.

“Worker sportsmen,” documents Gounot, “from the FST and the USSGT parade with a banner expressing the demand for the unity of the workers’ sports movement. After a speech by Henri Barbusse, who underlined the role of sporting youth as ‘one of the most important forces in the fight against fascism and capitalism,’ Albert Guillevic, secretary of the USSGT and co-president of the LSI announces for the first time that the USSGT is considering a merger with the FST. An important step towards the unity of the French workers’ sports movement…was thus taken.” By the end of the year, the two associations had united in the Fédération sportive et gymnique du travail, the Sports and Gymnastics Federation of Labor (FSGT).

Norway was the only LSI football team that accepted the RSI’s World Cup invitation, and they were joined in Paris by two other intriguing prospects: the unique territories of Saarland, a self-governing entity (incorporated into the Third Reich in 1935), and Alsace, reintegrated into France after WWI but endowed with some autonomous privileges. The groups were as follows:

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D |

| Soviet Union | Alsace | France | Czechoslovakia |

| Switzerland | England | Netherlands | Saarland |

| United States of America | Sweden | Norway | Spain |

As the only participant where the physical education of the working masses was given foremost importance by the state, the Soviet Union naturally went into this tournament as the obvious favourites, and the men from the East didn’t disappoint. Boasting three of the four Starostin brothers, Andrey, Alexander and Nikolai – all of whom would later do time in the Gulag on charges of embezzelment, theft and anti-Soviet agitation during WWII – the USSR easily dispatched Switzerland (11-0) in the quarters and Alsace (15-0) in the semis before, poetically, facing the LSI’s Norwegians, who had reached the final thanks to an automatic victory in the quarters (the Dutch turned up late) and a 13-0 demolition of Spain thereafter.

Merely a day after the Soviets had beaten Alsace, the Stade Buffalo in Montrouge played host to the final. Nobody wanted to miss this spectacle. “25,000,” wrote L’Humanité, “the vast majority of whom had rushed from offices, workshops, factories, as soon as the day was over and who invaded the metros, buses and special coaches with one direction…25,000 of them came to Buffalo last night, communists, socialists, the unorganised, seated side by side in the crowded aisles of the stadium.”

Though the Norwegians, too, were one of the tournament favourites, they couldn’t match the Soviets and ultimately fell to a straightforward 3-0 defeat. An own goal by Engen Svendsen and strikes from Aleksey Lapshin and Mikhail Yakushin sealed the deal for the Soviets. Yakushin would later become the head coach of Dynamo Moscow, overseeing their famous trip to England and leading them to six league titles before later taking charge of the USSR national team. Thus, the Soviets became the first workers’ world champions, though this title was never actually recognised, nor are the Paris fixtures recorded as official national team outings in the annals.

The French communist newspaper Regards hailed the occasion: “How different and base are the bourgeois – commercial – meetings compared to this splendid working-class gathering where camaraderie rubbed shoulders with quality, where solidarity shone!” Indeed, solidarity was the word on everyone’s lips at the anti-fascist Rally where, in addition to the “national” sides, also local and foreign workers’ clubs featured. In the spirit of solidarity, two Dutch sides, one socialist, the other communist, faced off at Stade Pershing to raise awareness for Ernst Thälmann, leader of the German Communist Party, interned and later murdered by the Nazis.

In the words of an FSGT publication, the Workers’ World Cup had “a political dimension justifying [its] existence which accompanied…the sporting dimension. The presence of foreign teams formed, in itself, the reason for the cup and not its consequence. Football was, indeed, one of the privileged vectors of internationalism…The symbolic power of the origin of the teams received was the major attraction of this type of event. Welcoming the USSR to Paris represented, for the French section of the RSI, a capital political gesture, embodying the desire to have sportingly and politically recognised “the fatherland of socialism.”

More so than that, however, did it signify a tremendous evolution of the French labour movement. A day after the World Cup final, the Rally concluded with a grand demonstration in the commune of Garches with some 50,000 spectators in attendance, where, according to Gounot, “unity was once again at the centre of the discourse.” Having achieved unification at the sporting level, the communists and socialists set about doing the same at the political level, forming the Front populaire two years later.

The Workers’ World Cup in Paris wasn’t the last major anti-fascist international sports competition before the war. That distinction belongs to the 1937 Workers’ Olympiad in Antwerp. Originally supposed to have taken place in Barcelona the previous year to counter the Nazi Olympics, the tournament was moved to Belgium following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War a few days before the People’s Olympiad was scheduled to start. A sign of the changing times and the dire situation of the leftist labour movement in the face of the deluge of international fascism, the Antwerp Olympiad was jointly organised by the LSI and the RSI.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, the Basque national team went on a charity tour of Europe, which included nine games in the USSR, to collect money for the families of fallen soldiers. The visitors lost only once during their time in the Soviet Union, a 6-2 defeat (on short rest and aided by poor refereeing) at the hands of the aforementioned Starostins and Spartak. Immediately after this match, Spartak were informed that they would represent the Soviet national team at the Antwerp Olympiad, ultimately winning the tournament with ease after sweeping aside workers’ teams from Denmark, France and Catalonia.

Spartak then continued on to Paris, where a small Workers’ World Cup was arranged by the FSGT as part of the famous International Exhibition. Having defeated an English workers’ team, Spartak again squared up with Catalonia in the final in front of 9000 spectators, and again the Soviets came out on top. The following year, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the founding of French workers’ sport, the FSGT again staged a “World Cup” tournament, described by René Rousseau, an important functionary at the time, as the most successful sporting event they had hitherto organised. Yet again, the Soviets, this time represented by Torpedo Moscow, triumphed after a meeting with Norway as they had four years before.

Though succeeding tournaments could never quite match the magnitude and splendour of the original 1934 edition (despite Rousseau’s assertion), they still retained the name, and they continued to be important occasions at the national level. The gains made by the Workers’ World Cup in welding together the labour movement were, however, ephemeral: in light of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, communists were purged from the FSGT. When the Nazis launched their invasion, the expelled communists formed the Free Sport network and helped to organise the Résistance, while the FSGT was eventually assimilated by the fascist occupiers and taken over by collaborationists. Thus, this brief but illuminating chapter of sporting history ended in the most barbaric fashion imaginable.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting my work with a small donation. Thank you!