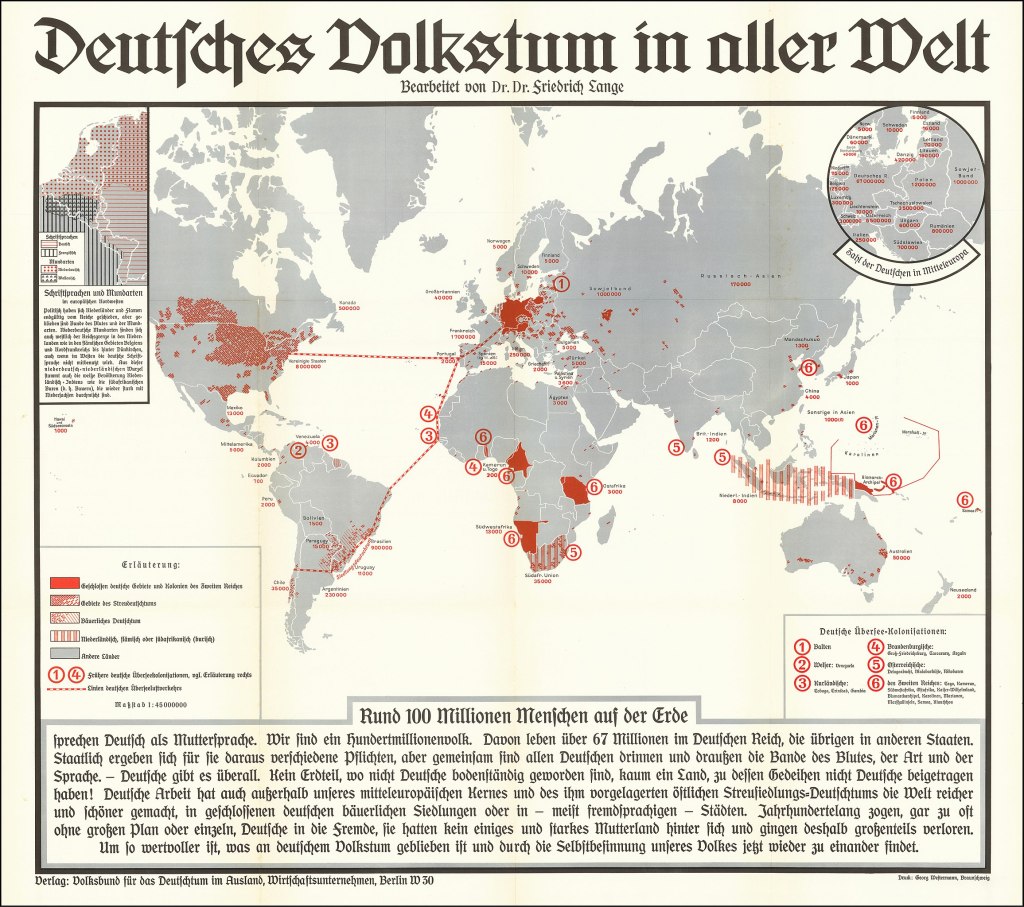

Colonialism and the history of Germany in the modern epoch are inextricably intertwined. From the first tentative attempts at acquiring territories in the Pacific in the 1870s and the construction of an empire with blood, iron and capitalist endeavour beginning in 1884 to the savage apotheosis of unfettered German barbarism following the establishment of the Third Reich and the putting into practice of the depraved Lebensraum theory – firmly rooted in the genocidal colonialism that preceded it – recent German history is stained with the blood of millions.

And yet, Germany’s colonial history features marginally at best in the cultural zeitgeist and general education. To be sure, liberal organizations like the state-controlled radio station Deutschlandfunk have appropriated talk of “decolonization” and stress Aufarbeitung (reappraisal) of the past, some, like the DFB, give development aid to former colonies and German governments at least now grudgingly acknowledge some of the atrocities committed – all factors that contribute to the frustratingly persistent myth that Germany has “atoned” for its wretched past – but actual education on the nation’s colonial history leaves a lot to be desired.

A survey by infratest dimap carried out in Berlin, the host city of the infamous conference that was so crucial in the “Scramble for Africa,” showed that out of the 1162 Berliners questioned, 49 per cent believed that education on Germany’s colonial crimes is inadequate. Most people are familiar with the fact that Germany had colonies, and they should be able to infer that violence was an integral, nay inherent, part of everyday life in them, but because Wilhemine colonialism was so short-lived – Germany had to relinquish its colonies during the First World War – and its legacy then either buried or actively extolled by West German historians after WWII, the extent to which Germany was implicated is not properly grasped, even though it was, at one point, the world’s third-biggest colonial power.

Ask a random German on the street and they most likely will never have heard of the genocides against the Herero and Nama or the mass murder of Damara and San communities in Namibia in which tens of thousands were slaughtered, driven into the desert to miserably succumb to dehydration or rounded up in concentration camps, and for which a formal apology and a guarantee of paying reparations (to be paid out over 30 years!) were only issued in 2021, after a decade of tedious negotiations. Having spent 12 years in the German education system, I can say that never once were we taught about these genocides or any other colonial crimes besides the Holocaust, and even that was tenuous at best and not put into a colonial context.

So when my friend Daniel McDermott, passing on a question from one of his students, asked me if Germany ever exported football to its colonies, I was stumped. I had never thought or heard about that, but my interest was piqued. Sports have always been a useful tool for both oppressors and oppressed, so naturally, they also played a role in Germany’s colonial enterprises. Daniel and I began scouring the web and scraping up every bit of information available to us. There wasn’t a lot to be found, truth be told, about the Wilhemine era that we’re interested in here. By comparison, there have been entire volumes written about football under the swastika.

Unfortunately, some resources I simply couldn’t get my hands on. The late Seth Mataba Boois and, it seems, New Life journalist Carlos Kambaekwa have both written books about the history of football in Namibia. Having been unable to get access to these works, I contacted one of Boois’ relatives to get some information on his illustrated history of Namibian football but did not get a reply. I also got in touch with Kambaekwa through his newspaper but this endeavour proved equally fruitless. He sent me an empty email with a PDF file attached in which he charged someone for a jazz concert. After informing him that I am, in fact, not the one who booked his band, I asked the questions I had posed in my initial email again, but the only thing I got back was a “thank you for your response.” I gave up at this point, so here’s what Daniel and I found on the internet:

From Colonialism and the Enactment of German Identity by Gertrud Pfister we learn that German colonization of Namibia, or what was then called Deutsch-Südwestafrika, actually began some forty years before it officially became a German “protectorate” (the favoured moniker for the colonies). “Since the 1840s the Protestant Rhineland Missionary Society (Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft) had played a particularly important role in South West Africa, covering the land with a network of missionary stations and furthering colonization…” Over the following decades, more settlers arrived and conflicts with autochthonous populations grew ever more acute, eventually exploding into open genocidal conflict with the arrival of Lothar von Trotha, who had already attained a murderous vita in East Africa and in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China.

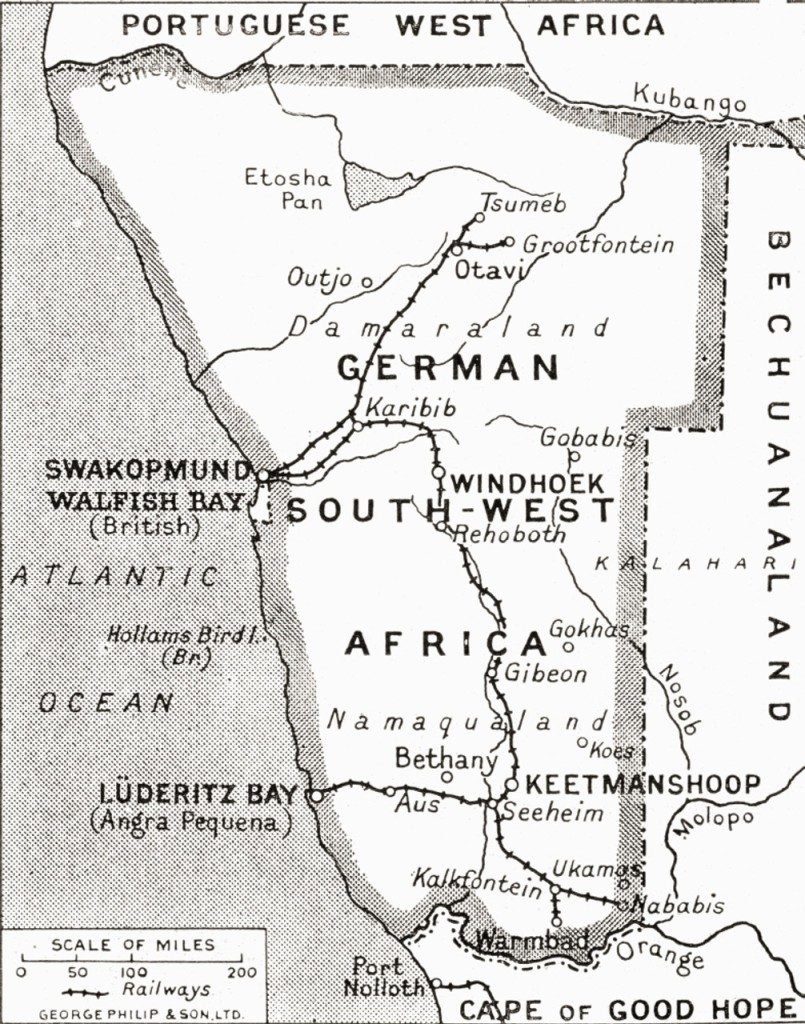

All the while, the settler-colonial project continued apace, entailing massive landgrabs and extermination. The surviving native populations were reduced to rightless, nameless labour power, toiling in mines or, in the case of Deutsch-Ostafrika (East Africa), on plantations. South West Africa was one of the few “protectorates” that experienced major German immigration (some 12,000 Germans lived there on the eve of WWI); it was, according to the inventor of Lebensraum, Friedrich Ratzel, the ideal destination for German colonists, Germany’s own American frontier – a precursor to, and testing ground of, the “Germanization” of Eastern Europe later carried out by the Nazis. “While admitting (and regretting) that it was too late for a German colony in an already settled North America,” writes Carroll P. Kakel III in The Holocaust as Colonial Genocide, “[Ratzel] favoured southwest Africa as a site of German colonization.” Accordingly, urban centers such as Windhoek, Swakopmund and Lüderitz grew exponentially.

“It was here,” documents Pfister, “that the clubs played an important role: the first rifle clubs were founded as early as 1895, war veterans’ clubs in 1897, and Turnvereine in 1898.” Turnen (gymnastics) was the national sport of Germany at the time, having been pushed into the limelight by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn during the Napoleonic occupation of Germany as a means of resistance and fostering unity, fitness and discipline of the German people. By the end of the 19th century, Turnen – at least when practised in a bourgeois context – had become inseparably linked with rabid German nationalism and the concomitant inclination toward imperialism and Prussian militarism, despite phoney proclamations of apoliticism by its central institutions.

German nationalism and colonialism were closely bound up; the colonies were to become a home away from home, a second Heimat for the colonizers and reservoirs of “Germanness.” The invaders, therefore, brought domestic traditions, habits and pastimes with them to the colonies in order to facilitate the creation of a feeling of Heimat in a land that so vastly differed from their Central European home. Against this backdrop, it is of little surprise that Turnen was the foremost sport exported to, and practised in, Southwest Africa. However, when we say exported, we mean, of course, that it was mainly reserved for the colonizers. Segregation was all-encompassing: Black people could only watch competitions from “outside the cordoned-off area” and although they sometimes “were taken along as porters on excursions, they did not count as participants.” Moreover, even before a race law officially banned mixed marriage, a man’s application to join a Turnverein could be rejected if his wife was not exclusively white.

German colonizers “established the first club in the colony, the ‘German Men’s Turnen Club,’ in Swakopmund in 1898. This was followed by the founding of a club in Windhuk in 1900. The ‘Lüderitzbucht Turnen Club for Men’ was founded in 1907 with 30 members, and further clubs followed in Karibib, Keetmanshoop, Usakos, and Tsumeb.” Turnen played a crucial role in the development of sports in German-occupied Southwest Africa. Its introduction and immense growth – “More than 500 men, around 10 percent of the German male population of South West Africa, belonged to the Turner movement.” – encouraged the institution of other disciplines, football being just one.

“In addition to the Turnen clubs, a number of sports clubs also provided an opportunity to take part in physical activities: for example, in Lüderitzbucht there was a football club (founded in 1909)…” This is the first concrete mention of a football club in Southwest Africa that we were able to locate. Giorgio Miescher and Dag Heinrichsen had claimed in Visualizing African football in apartheid Namibia that “the first ‘white’ club, the ‘Savages’ [sic], is recorded as having been formed in 1916, when the territory was already under South African rule.” Pfister’s date pushes the founding of out-and-out football establishments back to the times of German occupation, a fact also corroborated by statistics from the site RSSSF, which mentions an FK (Fußballklub?) Windhuk (likely founded in 1913) as well as a DFC (Deutscher Fußballclub?) Swakopmund prior to WWI.

Football, however, wasn’t merely played at designated Fußballclubs. Miraculously, the same site, RSSSF, contains invaluable data from early competitions in Namibia. From it, we learn that football was also played at SK/SV (Sportklub/Sportverein?) Omaruru (founded prior to 1913), 1. Kompanie Regenstein (presumably a military team) and MTV Usakos (MTV = Männer-Turn-Verein/men’s gymnastics club), the most successful football side of the pre-WWI era.

Successful? How so? Was there a league? No, that would have probably been an unfeasible logistical impossibility considering the sheer vastness of Namibia, but there were friendly fixtures and even a cup competition, the Südwest-Pokal, played from 1910 through 1913, the final three of which were all claimed by Usakos (the inaugural champions are unknown). In the spring of 1914, according to RSSSF, an umbrella organization was founded, the Verband deutsch-südwestafrikanischer Ballspielvereine, but the outbreak of the war put a swift end to its existence.

Football was an important lever of social control in neighbouring colonies. In British and French territories, the indigenous population watched how European soldiers and miners played and then proceeded to emulate them. This was, to some extent, encouraged by the colonizers since sport, echoing the words of one German bourgeois official, made the youth “forget about its miserable existence.” The spectre haunting Europe, the ubiquitous fear of a communist uprising, was also imported to the colonies and, therefore, the native populations and subaltern classes of colonizers were exhorted to spend their free time exercising.

In the long run, the colonizers, famously, couldn’t curb the proliferation of Marxist ideas, and clubs eventually became vital centers of community and hotbeds of anti-colonial sentiment, but this approach nevertheless seemed to yield some positive results early on: in Kolonialsport in Südwest-Afrika, Dr. Armin Ader notes that “statistics from colonial times give the impression that the spread of the game of football caused a reduction in crime and alcoholism amongst African teenagers.” He does not give a date for when those statistics were collected, though, so we don’t know whether he is talking about German colonies or the territories of other colonial powers.

Pfister contends that, unlike sports in English and French colonies, “Turnen was used not as a means of disciplining, controlling, and educating the native population, but rather as an instrument of segregation and exclusion.” The same likely applied to football. How widespread, if at all, the game was in African communities during German occupation we do not know. The first Black clubs were established under the South African apartheid regime (there were more than 20 by the 1960s), and only in 1975 did a Black team face off against a white side in any official capacity.

Over the course of the century since German occupation ended, some clubs from those days have fallen by the wayside, while others still exist, albeit in a different form. One of those is SK Windhoek, the successor of Turnverein Windhoek, likely the “club [founded] in Windhuk in 1900” Pfister mentioned. For a long time, SKW was a regular fixture in the top division of Namibian football. Between 2002 and 2010 the side was coached by Richard Starke, the father of Sandra and Manfred, third-generation white Namibians educated at a private German school established during colonial times, who now play professionally in the country of their great-grandfather’s birth, with the former representing reigning Frauen-Bundesliga champions Wolfsburg and the latter featuring for 3. Liga side Oldenburg and the Namibian national team – they are two of the small number of Namibians playing professionally outside of southern Africa.

Though Namibia is now a proud and independent state, some colonial vestiges – like Sandra’s and Manfred’s school – persist to this day. Whites only constitute a tiny percentage of the Namibian population, yet they own more land than any other demographic as well as controlling much of the country’s wealth. The justified outrage from indigenous communities over a lack of reparations should also not be drowned out by the development aid given by German organizations. With the two countries’ histories so deeply entangled, there is much more to be done before the myth that Germany has atoned for its past sins turns into reality.

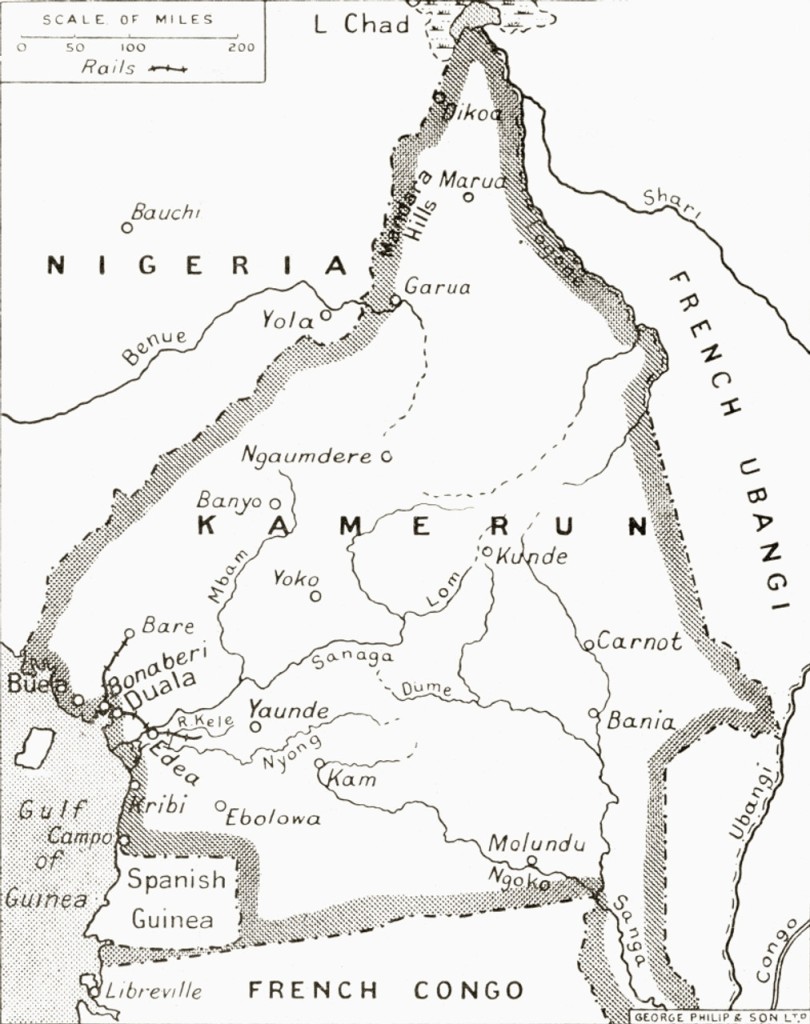

Information on football in other German colonies is even scanter than it is for Namibia. In Togo, a model colony according to German and foreign imperialists and Cold War neo-imperialists, there was – unlike in neighbouring Ghana – no meaningful footballing development until the 1940s. This has been blamed on French influence, which is interesting because in Cameroon, also a former German colony, football was introduced in the coastal town of Douala in the Francophone part as early as the 1920s. More intriguingly, in Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, it is claimed that it was actually German colonizers who imported football already in the 1880s, which, though not outside the realm of possibility, seems extremely early considering that football had only made its way to Germany a decade earlier and was still anything but the accessible and popular game of the people that it would become later.

That said, it’s important to remember that football and sports in general were introduced by individual actors and not through state-sponsored or coordinated campaigns, hence the significant temporal differences of when this or that sport made its way to this or that country. So it’s certainly possible that some Germans had kickabouts in Cameroon in the 1880s, but without concrete evidence (and taking into account the comparatively small magnitude of German immigration), it seems pretty implausible, and even if they did, to say that they introduced the game would be a stretch since it evidently wasn’t played in any organized fashion or caught on until much later.

As far as we can tell, football did not play any significant role in German East Africa, which today straddles Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. Officially, the first football clubs in Tanzania were formed in the 1920s and enjoyed financing from businesses or government departments. In Rwanda, the game was most likely introduced by Catholic missionaries in the same decade. Similarly, missionaries also brought the game to Burundi, although much later, in 1936. Considering, however, that a few thousand Germans settled in East Africa, it’s probably fair to assume that they also played football – perhaps even within the framework of organized clubs – in bustling urban centers such as Dar es Salaam and Tanga, as they did in Namibia. But again, without any evidence, this is purely conjecture.

Across the Indian Ocean, evidence of German football is sparse, too. In China, football-like games had already been played for over a thousand years when foreigners and missionaries introduced the modern game in the late 19th century. Some Brits set up a league in Shanghai in 1907 and the game subsequently spread all along the eastern coast, including to German-occupied Tsingtau (now Qingdao), which, like Togoland, was supposed to be a model colony, built up and developed to prove that Germany was capable of competing with the established colonial powers. Here, too, traditions – and even German trees – were imported to create a feeling of Heimat. In Far Away at Home in Qingdao, Sabina Groeneveld mentions in passing that football was one of the “typical leisure activities” of the Germans living in Qingdao, but that is all the information we have.

There is nothing to be found regarding the small Pacific islands and archipelagos other than an uncited remark on Wikipedia that soccer was first played in Nauru in the 1890s. According to the Papua New Guinea Football Association, the game “was first introduced in PNG in 1884 in Finschafen, Morobe Province by the German missionaries of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Germany.” Again, this seems quite early – in fact, this is the very year that “Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land” was claimed by the German New Guinea Company – but it’s certainly possible.

Interestingly, Papua New Guinea’s 1977 national champions went by the name of Germania FC and were based in the capital, Port Moresby, an area that was never under German control. I was unable to find anything on the club, but it’s possible – with a name like that perhaps even likely – that it was founded by Germans. Even after Germany was forced to relinquish its overseas territories, Germans continued to emigrate and colonize.

German Mennonites, for example, colonized several regions in Paraguay in the 1920s and now run two football federations replete with clubs boasting names such as Friesland, Fernheim, Sommerfeld, Neuland and Deutscher Sportverein Independencia. Several years earlier, German immigrants had begun making inroads into the sporting landscape of other South American countries. Isabelle Rispler writes: “German-speakers who left Central Europe in the nineteenth century predominantly chose the United States as their migration destination, but lower numbers also went to Brazil, Chile, and Argentina.” She continues: “In Argentina…there were a German Soccer Club Buenos Aires and a Soccer Club Victoria by 1907.” In Brazil’s Porto Alegre, Germans (co-)founded the city’s first two football clubs on the same day, September 15, 1903: Fussball Club Porto Alegre, which ceased to exist in 1944, in the morning and the famous Grêmio at night.

In conclusion, it is evident that the topic of football in the Wilhemine colonies is, to use a German expression, a Forschungsdesiderat, a scholarly blindspot. Whether this is due simply to a lack of interest or a lack of documentation I do not know. But considering the exhaustive amount of literature that exists on Turnen, for example, this is quite surprising.

I hope that this article perhaps motivated someone to dig deeper and sift through the archives or an institution to provide funding for such an endeavour. Hell, if supplied the financial resources, I would do the digging myself! A deeper investigation of this matter could give us a more precise understanding of everyday life in the colonies and, more importantly, it could unearth more information on the earliest history of football in indigenous communities in Africa, Asia and Oceania.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting my work with a small donation. Thank you!